Quite a bit of my research and public writing in the last few years has been on the topic of college closures and institutions in financial distress. I’m also a bit on the nerdy side, as evidenced by the fact that I am still trying to figure out who sent us a Stata onesie when our first child arrived several years ago. So it’s not a surprise that I jumped on the opportunity to be able to visit the former Iowa Wesleyan University while taking a family trip this summer.

A bit of the backstory on Iowa Wesleyan: it was founded in 1842 in Mount Pleasant, Iowa as the first co-educational private institution west of the Mississippi River. After Parsons College in nearby Fairfield suddenly collapsed and closed in 1973, it was the only traditional four-year institution within a 50-mile radius. And the two closest larger institutions (the University of Iowa and Truman State University in Missouri—my alma mater) are relatively selective, leaving Iowa Wesleyan with a market niche.

But as the tri-state area of southeast Iowa, northeast Missouri, and western Illinois saw a decline in the number of high school graduates, the university struggled. The university received $26 million in a US Department of Agriculture loan to help avoid a closure in 2018 (helped by the Secretary of Agriculture’s wife being on the board. But even as enrollment increased (thanks to athletics), tuition revenue did not. A last-ditch appeal to Iowa’s governor for $12 million failed, and the college closed in 2023; the campus then went to the USDA as its main creditor.

Figuring out what to do with a closed college campus is always a challenge, as these campuses are built for a particular purpose and deferred maintenance is often an issue. Campuses in rural areas face particular concerns, as it is much harder to attract a buyer when there is a smaller population base nearby. Mount Pleasant was fortunate to find several buyers for parts of the campus when the USDA put it up for sale. The primary owner of the campus is the local school district, which bought athletic facilities and an auditorium. The district is also considering putting an elementary school on the site to use existing facilities as much as possible.

Here are some pictures of the campus, and a big thank you to P.E.O. International (my wife is a member of this group that supports women’s education) for the opportunity to tour the campus’s oldest building. The campus grounds are neat and tidy, but there are certainly signs of deferred maintenance issues throughout.

The Iowa Wesleyan signs have been replaced with signs for the local school district.

The main quad of campus. It still looks like a great place to hang out.

The original building on IWU’s campus. It is stately, but also has maintenance issues.

Stained glass windows just don’t exist like this any more.

Providing a sense of the facilities challenges of a campus that is well over 100 years old.

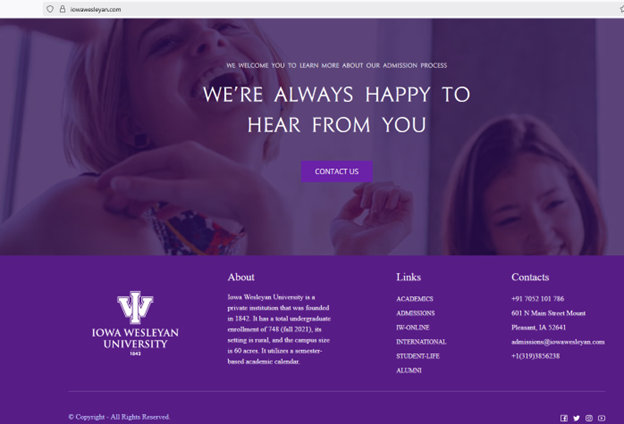

And as an aside, a Google search for Iowa Wesleyan shows the following website as the top result. Note the .com on the website and the random international phone number (from India) at the bottom right corner. It looks like a fraud.

The admissions page is actually active, but it seems even more dubious than the rest of the site. Someone duplicated the website for their own uses.