As the academic summer quickly wraps up (nine-month faculty contracts at Tennessee begin on August 1), I am working on wrapping up some research projects while also simultaneously preparing for new ones. One of the projects that is near completion (thanks to Arnold Ventures for their support of this work) is examining the prevalence and implications of the federal government’s heightened cash monitoring (HCM) policy in higher education.

In the spring, I shared my first paper on the topic, which examined whether HCM placement was associated with changes to institutional financial patterns or student outcomes. We found generally null findings, which matches much of a broader literature on the effects of accountability in higher education that are not directly tied to the loss of federal financial aid. In this post, I am sharing two more new papers.

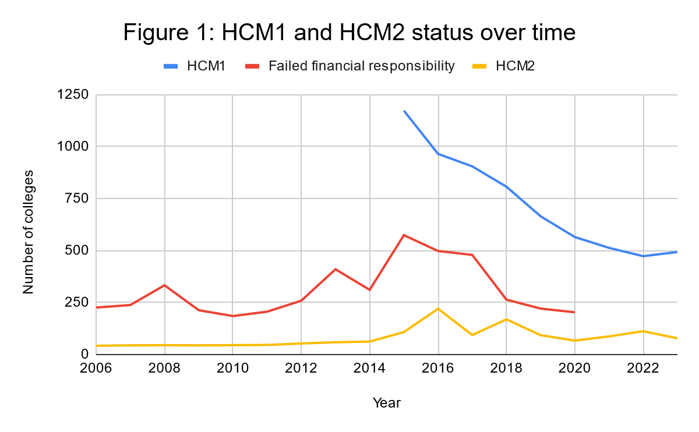

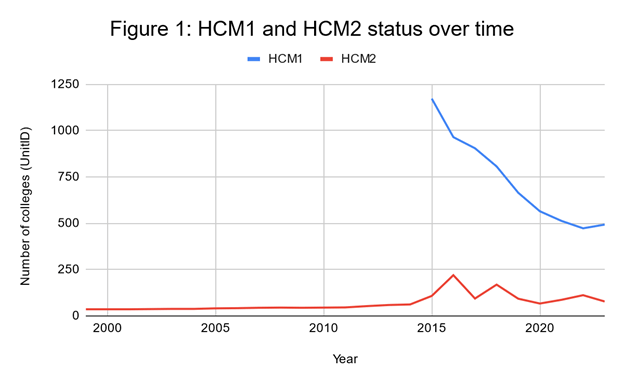

The first paper descriptively examines trends in HCM status over time, the interaction with other federal accountability policies, and whether colleges placed on HCM tend to close. There are two levels of HCM: HCM1 requires additional oversight, while the more severe HCM2 requires colleges to pay out money to students before being reimbursed by Federal Student Aid. As shown below, there was a spike in usage of HCM2 status around 2015, which was also the first year that HCM1 data were made publicly available by the Department of Education.

Colleges end up on HCM1 and HCM2 for much different reasons. The less severe HCM1 is dominated by colleges with low financial responsibility scores, while more serious accreditation and administrative capacity concerns are key reasons for HCM2 placement. Additionally, colleges on HCM2 tend to close at higher rates than colleges on HCM1.

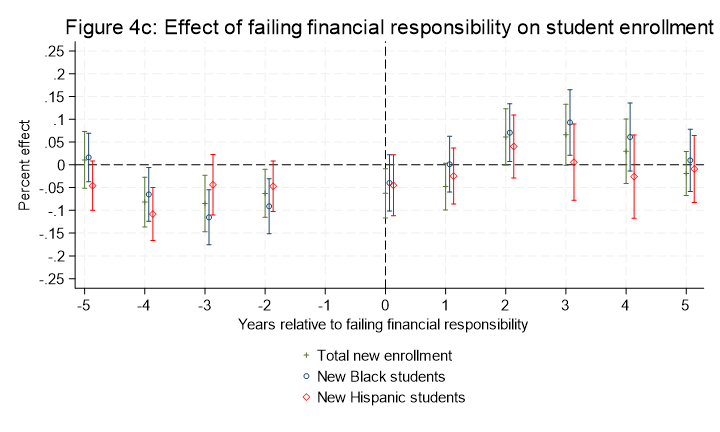

The second paper builds on the other research from this project to examine whether student enrollment patterns are affected by signals of institutional distress. The motivation for this work is that in an era of heightened concerns about the stability of colleges, students may seek to enroll elsewhere if a college they are attending (or considering attending) displays warning signs. On the other hand, colleges may redouble their recruitment efforts to try to dig themselves out of the financial hole.

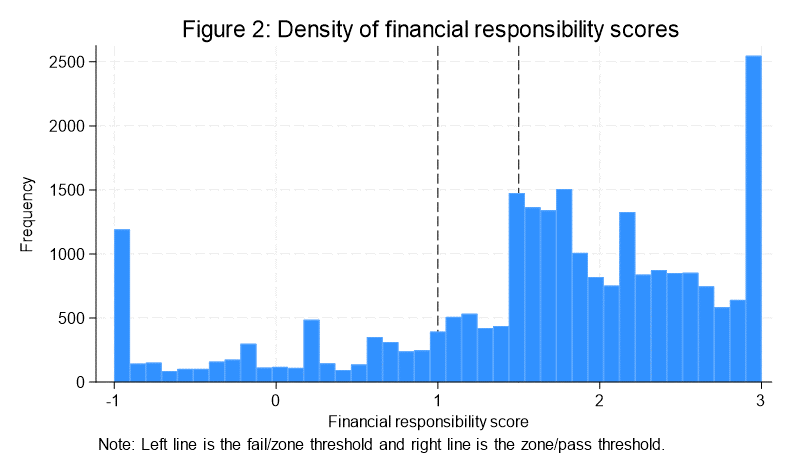

We examined these questions using two different accountability thresholds. The first was to compare colleges on HCM2 to colleges with a failing financial responsibility score, as HCM2 is a much smaller list of colleges and comes with restrictions on institutional operations. The second was to compare colleges that just failed the financial responsibility metric to colleges that were in an oversight zone that allowed them to avoid being placed on HCM1 if they posted a letter of credit with the Department of Education. As the below figure shows, there is not a huge jump in the number of colleges that barely avoided failing (the left line)—and that allows for the use of a regression discontinuity design.

After several different analyses, the key takeaway is that students did not respond to bad news about their college’s situation by changing their enrollment patterns. If anything, enrollment may have increased slightly in some cases following placement on HCM2 or receiving a failing financial responsibility score (such as in the below figure). This finding would be consistent with students never hearing about this news or simply not having other feasible options of where to attend. I really wonder if this changes in the future as more attention is being paid to the struggles of small private colleges in particular.

I would love your feedback on these papers, as well as potential journals to explore. Thanks for reading!