I hope that everyone had a restful break and is excited to come back for what will undoubtedly be an eventful year in the world of higher education. This spring is going to be quite busy for me with three faculty searches, our once-a-decade academic program review, the most travel for presentations that I have had since before the start of the pandemic, and responding to a host of media and policymaker requests about what will be happening over the next few months.

To add to the excitement of the coming few months, I have the pleasure of teaching my PhD class in higher education finance again. As a department head, I typically only get to teach one class per year. This is my absolute favorite class to teach, as it aligns well with my research areas and on-the-ground experience as a cog in the bureaucratic machine at two different universities. Each time, I have updated the readings considerably as the field is moving quickly and I figure out what works best for the students. I use articles, working papers, news coverage, and other online resources to provide a current look at the state of higher education finance.

Here is the reading list I am assigning my students for the course (see here for past versions and other teaching musings). I link to the final versions of the articles whenever possible, but those without access to an academic library should note that earlier versions of many of these articles are available online via a quick Google search.

Happy reading!

The higher education finance landscape and data sources

Burke, L. (2023). Department of Education. In P. Dans & S. Groves (Eds.), Mandate for leadership: The conservative promise (pp. 319-362). The Heritage Foundation.(link)

Schanzenbach, D. W., Bauer, L., & Breitwieser, A. (2017). Eight economic facts on higher education. The Hamilton Project. (link)

Webber, D. A. (2021). A growing divide: The promise and pitfalls of higher education for the working class. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 695, 94-106. (link)

Recommended data sources:

College Scorecard: https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/ (underlying data at https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/data/)

Equality of Opportunity Project: http://www.equality-of-opportunity.org/college

IPEDS: https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/use-the-data

NCES Data Lab: https://nces.ed.gov/datalab/index.aspx

Postsecondary Value Commission’s Equitable Value Explorer: https://www.postsecondaryvalue.org/equitable-value-explorer/

ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer: https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/

Urban Institute’s Data Explorer: https://educationdata.urban.org/data-explorer/colleges/

Institutional budgeting

Barr, M.J., & McClellan, G.S. (2010). Understanding budgets. In Budgets and financial management in higher education (pp. 55-85). Jossey-Bass. (link)

Jaquette, O., Kramer II, D. A., & Curs, B. R. (2018). Growing the pie? The effect of responsibility center management on tuition revenue. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(5), 637-676. (link)

Rutherford, A., & Rabovsky, T. (2018). Does the motivation for market-based reform matter? The case of responsibility-centered management. Public Administration Review, 78(4), 626-639. (link)

University of Tennessee System’s FY2025 budget: https://finance.tennessee.edu/budget/documents/

University of Tennessee System’s FY2023 annual financial report: https://treasurer.tennessee.edu/reports/

UTK’s Budget Allocation Model (responsibility center management) website: https://budget.utk.edu/budget-allocation-model/

Higher education expenditures

Archibald, R. B., & Feldman, D. H. (2018). Drivers of the rising price of a college education. Midwestern Higher Education Compact. (link)

Commonfund Institute (2024). 2024 higher education price index. (link)

Griffith, A. L., & Rask, K. N. (2016). The effect of institutional expenditures on employment outcomes and earnings. Economic Inquiry, 54(4), 1931-1945. (link)

Hemelt, S. W., Stange, K. M., Furquim, F., Simon, A., & Sawyer, J. E. (2021). Why is math cheaper than English? Understanding cost differences in higher education. Journal of Labor Economics, 39(2), 397-435. (link)

Korn, M., Fuller, A., & Forsyth, J. S. (2023, August 10). Colleges spend like there’s no tomorrow. ‘These places are just devouring money.’ The Wall Street Journal. (link)

The financial viability of higher education

Britton, T., Rall, R. M., & Commodore, F. (2023). The keys to endurance: An investigation of the institutional factors relating to the persistence of Historically Black Colleges and Universities. The Journal of Higher Education, 94(3), 310-332. (link)

Ducoff, N. (2019, December 9). Students pay the price if a college fails. So why are we protecting failing institutions? The Hechinger Report. (link)

Jesse, D., & Bauman, D. (2023, November 13). This small college was out of options. Will its creditors give it a break? The Chronicle of Higher Education. (link)

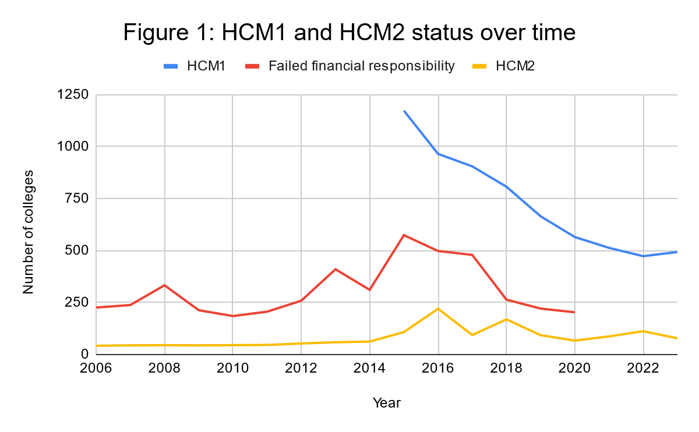

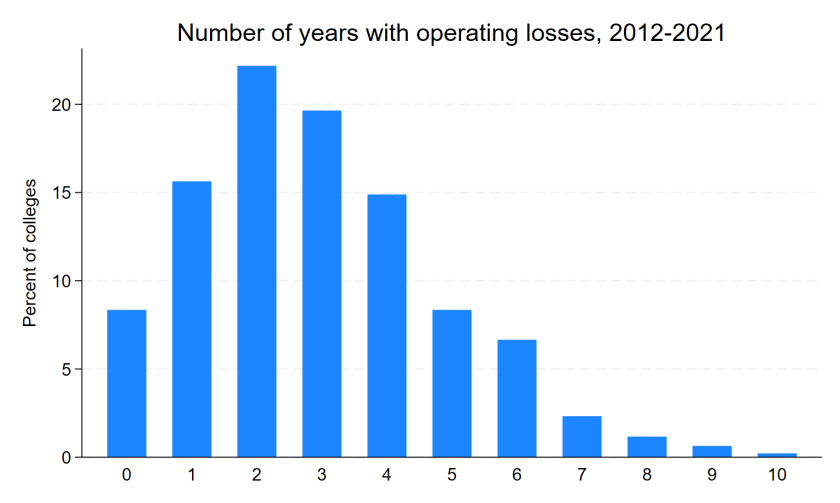

Kelchen, R., Ritter, D., & Webber, D. A. (2024). Predicting college closures and financial distress. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 33216. (link)

Tarrant, M., Bray, N., & Katsinas, S. (2018). The invisible colleges revisited: An empirical review. The Journal of Higher Education, 89(3), 341-367. (link)

State sources of revenue

Chakrabarti, R., Gorton, N., & Lovenheim, M. F. (2020). State investment in higher education: Effects on human capital formation, student debt, and long-term financial outcomes of students. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 27885. (link)

Gándara, D. (2024). “One of the weakest budget players in the state”: State funding of higher education at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 46(3), 458-482. (link)

Kelchen, R., Ortagus, J. C., Rosinger, K. O., Baker, D., & Lingo, M. (2024). The relationships between state higher education funding strategies and college access and success. Educational Researcher, 53(2), 100-110. (link)

Kunkle, K. (2024). State higher education finance: FY 2023. State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. (link)

Ortagus, J. C., Kelchen, R., Rosinger, K. O., & Voorhees, N. (2020). Performance-based funding in American higher education: A systematic synthesis of the intended and unintended consequences. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(4), 520-550. (link)

Tennessee’s outcomes-based funding formula: https://www.tn.gov/thec/bureaus/ppr/fiscal-policy/outcomes-based-funding-formula-resources/2020-25-obf.html

Federal sources of revenue

American Enterprise Institute, EducationCounsel, and The Century Foundation (2024). Taking a balanced approach: Six proposals to fairly and effectively reform federal graduate financing policy from across the ideological spectrum. (link)

Bergman, P., Denning, J. T., & Manoli, D. (2019). Is information enough? The effect of information about education tax benefits on student outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 38(3), 706-731. (link)

Black, S. E., Turner, L. J., & Denning, J. T. (2023). PLUS or minus? The effect of graduate school loans on access, attainment, and prices. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 31291. (link)

Graddy-Reed, A., Feldman, M., Bercovitz, J., & Langford, W. S. (2021). The distribution of indirect cost recovery in academic research. Science and Public Policy, 48(3), 364-386. (link)

Kelchen, R., & Liu, Z. (2022). Did gainful employment regulations result in college and program closures? Education Finance and Policy, 17(3), 454-478. (link)

College pricing, tuition revenue, and endowments

American Council on Education (2024). Understanding college and university endowments. (link)

Bauman, D. (2024, April 22). Amid financial headwinds, some colleges are digging deeper into their endowments. Will more follow? The Chronicle of Higher Education. (link)

Delaney, T., & Marcotte, D. E. (2024). The cost of public higher education and college enrollment. The Journal of Higher Education, 95(4), 496-525. (link)

Kelchen, R., & Pingel, S. (2024). Examining the effects of tuition controls on student enrollment. Research in Higher Education, 65, 70-91. (link)

Knox, L. (2023, December 4). Seeking an enrollment Hail Mary, small colleges look to athletics. Inside Higher Ed. (link)

Ma, J. Pender, M., & Oster, M. (2024). Trends in college pricing and student aid 2024. The College Board. (link)

Webber, D. A. (2017). State divestment and tuition at public institutions. Economics of Education Review, 60, 1-4. (link)

Financial aid policies, practices, and impacts

Anderson, D. M., Broton, K. M., Goldrick-Rab, S., & Kelchen, R. (2020). Experimental evidence on the impacts of need-based financial aid: Longitudinal assessment of the Wisconsin Scholars Grant. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 39(3), 720-739. (link)

Billings, M. S., Clayton, A. B., & Worsham, R. (2022). FAFSA and beyond: How advisers manage their administrative burden in the financial aid process. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 51(2), Article 2. (link)

Dynarski, S., Page, L. C., & Scott-Clayton, J. (2022). College costs, financial aid, and student decisions. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 30275. (link)

LaSota, R. R., Polanin, J. R., Perna, L. W., Austin, M. J., Steingut, R. R., & Rodgers, M. A. (2022). The effects of losing postsecondary student grant aid: Results from a systematic review. Educational Researcher, 51(2), 160-168. (link)

Page, L. C., Sacerdote, B. I, Goldrick-Rab, S., & Castleman, B. L. (2023). Financial aid nudges: A national experiment with informational interventions. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 45(2), 195-219. (link)

Student debt and financing college

Black, S. E., Denning, J. T., Dettling, L. J., Goodman, S., & Turner, L. (2020). Taking it to the limit: Effects of increased student loan availability on attainment, earnings, and financial well-being. American Economic Review, 113(12), 3357-3400. (link)

Boatman, A., Evans, B. J., & Soliz, A. (2017). Understanding loan aversion in education: Evidence from high school seniors, community college students, and adults. AERA Open, 3(1), 1-16. (link)

Levine, P. B., & Ritter, D. (2024). The racial wealth gap, financial aid, and college access. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 43(2), 555-581. (link)

Looney, A., & Yannelis, C. (2024). What went wrong with federal student loans? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 38(3), 209-236. (link)

Monarrez, T., & Turner, L. J. (2024). The effect of student loan payment burdens and nonfinancial frictions on borrower outcomes. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Working Paper 24-08. (link)

Free college/college promise programs

Carruthers, C. K., Fox, W. F., & Jepsen, C. (2023). What Knox achieved: Estimated effects of tuition-free community college on attainment and earnings. The Journal of Human Resources. (link)

Gándara, D., & Li, A. Y. (2020). Promise for whom? “Free-college” programs and enrollments by race and gender classifications at public, 2-year colleges. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(4), 603-627. (link)

Monaghan, D. B. (2023). How well do students understand “free community college”? Promise programs as informational interventions. AERA Open, 9(1), 1-13. (link)

Murphy, R., Scott-Clayton, J., & Wyness, G. (2017). Lessons from the end of free college in England. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. (link)

Perna, L. W., Leigh, E. W., & Carroll, S. (2018). “Free college:” A new and improved state approach to increasing educational attainment? American Behavioral Scientist, 61(14), 1740-1756. (link)

Map of college promise/free college programs (Penn AHEAD) (link)

Returns to education

Conzelmann, J. G., Hemelt, S. W., Hershbein, B. J., Martin, S., Simon, A., & Stange, K. M. (2023). Grads on the go: Measuring college-specific labor markets for graduates. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. (link)

Darity, Jr., W. A., & Underwood, M. (2021). Reconsidering the relationship between higher education, earnings, and productivity. Postsecondary Value Commission. (link)

Deterding, N. M., & Pedulla, D. S. (2016). Educational authority in the “open door” marketplace: Labor market consequences of for-profit, nonprofit, and fictional educational credentials. Sociology of Education, 89(3), 155-170. (link)

Ma, J., & Pender, M. (2023). Education pays 2023: The benefits of higher education for individuals and society. The College Board. (link)

Zhang, L., Liu, X., & Hu, Y. (2024). Degrees of return: Estimating internal rates of return for college majors using quantile regression. American Educational Research Journal, 61(3), 577-609. (link)