This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Ahead of the Democratic National Convention – on July 5 – Hillary Clinton announced a set of new proposals on higher education. Key measures included eliminating college tuition for families with annual incomes under US$125,000 and a three-month moratorium on federal student loan payments.

Clinton’s original plan had called for the federal government and states to fund public colleges so students wouldn’t have to borrow to cover tuition if they worked at least 10 hours per week.

The revised higher education plan represents a clear leftward shift and is likely an effort to solidify her support among still-skeptical young supporters of Bernie Sanders.

As a researcher of higher education finance, my question is whether these proposals, estimated to cost $450 billion over the next 10 years, will benefit enough of the over 10 million college-going voters struggling to repay loans.

How student loan interest rates work

Typically, students pay interest rates set by Congress and the president on their federal student loans.

Over the last decade, interest rates for undergraduate students have fluctuated between 3.4 percent and 6.8 percent. Rates for federal PLUS loans have ranged from 6.3 percent to 8.5 percent. Federal PLUS loans require a credit check and are often cosigned by a parent or spouse. Federal student loans do not have those requirements.

While students pay this high a rate of interest, rates on 15-year mortgages are currently below three percent.

Application form image via www.shutterstock.com

It is also important to note the role of private loan companies that have recently entered this market. In the last several years, private companies such as CommonBond, Earnest and SoFi as well as traditional banks have offered to refinance select students’ loans at interest rates that range from two percent to eight percent based on a student’s earnings and their credit history.

However, unlike federal loans (which are available to nearly everyone attending colleges participating in the federal financial aid programs), private companies limit refinancing to students who have already graduated from college, have a job and earn a high income relative to the monthly loan payments.

Analysts have estimated that $150 billion of the federal government’s $1.25 trillion student loan portfolio – or more than 10 percent of all loan dollars – is likely eligible for refinancing through the private market – much of it likely for graduate school.

Many Democrats, such as Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, have pushed for all students to receive lower interest rates on their federal loans for years. Republican nominee Donald Trump too has questioned why the federal government profits on student loans – although whether the government actually profits is less clear.

Issues with refinancing of loans

Interest rates on student loans were far higher five to 10 years ago (ranging from 6.8 percent to 8.5 percent based on the type of loan). Allowing students to refinance at current rates ranging from 3.76 percent to 6.31 percent would mean that some students could possibly lower their monthly payments.

But the question is, how many students will benefit from the refinance?

Robert Galbraith/Reuters

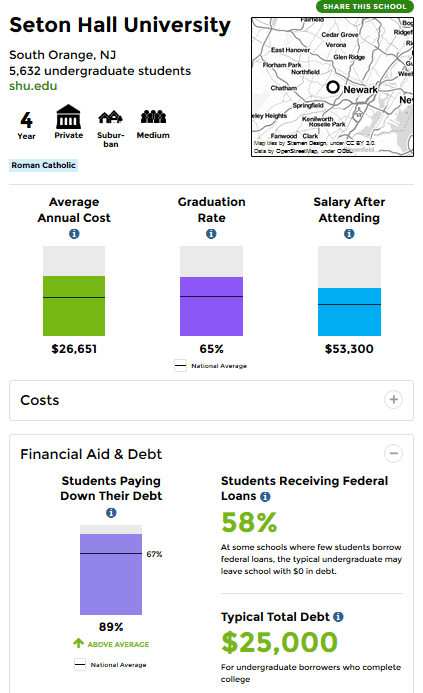

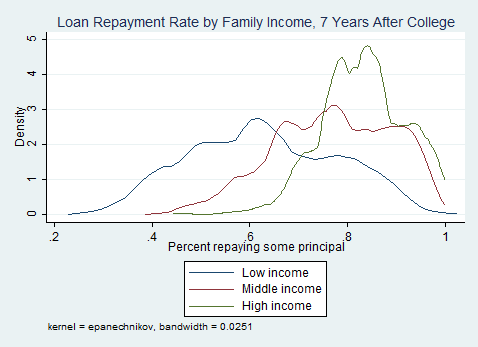

Students with the most debt are typically college graduates and are the least likely to struggle to repay their loans. In addition, they can often refinance through the private market at rates comparable to what the federal government would offer.

Struggling borrowers, on the other hand, already have a range of income-driven repayment options through the federal government that can help them manage their loans. Some of their loans could also be forgiven after 10 to 25 years of payments.

Furthermore, the majority of the growth in federal student loans is now in income-driven plans, making refinancing far less beneficial than it would have been 10 years ago. Under income-driven plans, monthly payments are not tied to interest rates.

So, on the face of it, allowing students to refinance federal loans would appear to be beneficial. But, in reality, because of the growth of private refinancing for higher-income students and the availability of income-driven plans for lower-income students, relatively few students would likely benefit.

Why implementing a moratorium will be hard

On the proposed three-month moratorium, Clinton has said she could proceed on it via executive action as soon as she takes office – potentially making it the most important part of her plan.

During these three months, the Department of Education and companies servicing student loans would reach out to borrowers to help them enroll in income-driven plans that would reduce monthly payments.

So, would a moratorium on student loan payments help struggling borrowers?

The challenge is that reaching out to each and every one of the estimated 41.7 million students with federal student loans in a three-month period would be a Herculean task given the Department of Education’s available resources.

Currently, about one-fifth of the federal government’s student loan portfolio, or $260 billion is in deferment or forbearance, meaning that students are deferring payments until later.

To put this another way, about 3.5 million loans are at least 30 days behind on payments, and eight million loans are in default. This could mean that those students haven’t made a payment in at least a year.

Just trying to contact 3.5 million students in a three-month window would be a difficult proposition, let alone contacting the millions of additional students who are putting off payments until later.

Andrew Burton/Reuters

There are also other issues that Department of Education staffers and loan servicers must deal with that may be more important than an overall repayment moratorium.

Nearly 60 percent of students who were enrolled in income-driven repayment plans fail to file the annual paperwork. That paperwork is necessary if students are to stay in those programs. And failure to do so results in many students facing higher monthly payments.

Focus needed on most in need students

In my view, Clinton’s proposals of allowing students to refinance their loans at lower rates through the federal government and a three-month moratorium on payments are unlikely to benefit that many students.

Hopefully, the Clinton campaign will focus later versions of the proposal on borrowers most in need of assistance. If not, this could present an opportunity for the Trump campaign to release a coherent higher education agenda.

![]()