In a conclusion to one of the most consequential Supreme Court sessions in many years, the Court released an opinion today on the Biden administration’s proposed plan to forgive up to $20,000 in federal student loan debt per borrower. After dismissing one case due to lack of standing from the plaintiffs, the Court voted 6-3 to block forgiveness in the second case (giving standing based on the servicer MOHELA).

This decision will have major implications for higher education policy. Here are the things that I will be looking for in the coming months and years:

Restarting student loan repayment was already going to be a nightmare, and this creates additional challenges. The first challenge is the sheer number of borrowers re-entering repayment. Roughly 43 million Americans have federal student debt, and the Biden administration estimated that about 20 million would have their loans completely forgiven by their proposal. I have little confidence that the Department of Education, student loan servicers, and colleges can smoothly handle 23 million borrowers that would have remained, let alone 43 million. Federal Student Aid badly needed additional resources to manage a return to repayment, but Republicans were only willing to provide the funds if it came with a rider blocking its use on debt relief. Since both parties agreed on no riders in last year’s omnibus spending bill, no additional funding was provided.

In an overlooked item due to yesterday’s important decision on college admissions, the Department of Education released information about how they plan to manage the return to repayment. ED plans to give a 90-day grace period for missed payments and is considering future grace periods. Needless to say, Republicans are not happy and may go to court to stop grace periods based on the agreement in this summer’s debt ceiling legislation.

How many borrowers are willing to start making payments? There is going to be a group of people who are livid about having to resume payments after not getting the loan forgiveness they were expecting. I am expecting a substantial group of borrowers to not make any payments until they get to the brink of default—which could take a while. These borrowers may still hold out hope for another forgiveness effort (more on that in the next section) and they may not proactively reach out to servicers to update their information if they have moved since March 2020. A particularly interesting group is the 20 million students who would have received complete forgiveness, as the frustration factor is likely higher among this group than among students who knew they would still have a balance remaining under this plan.

As a note, with income-driven repayment, students at least in theory should be able to start making some payments. But adding an expense back to the monthly budget is painful and income-driven repayment is still complicated to navigate. So there will be challenges even among people who are not as upset about this decision.

How will Democrats respond? The progressive wing of the Democratic Party has been pressuring the Biden administration to forgive all student debt and immediately pivot to using the Higher Education Act instead of the HEROES Act. That is likely not happening given today’s court decision. But a few moderate Democrats voted in favor of a Republican-led resolution disapproving of debt forgiveness and ending the repayment pause. The Biden administration will point to its expanded income-driven repayment plan, which could also face legal challenges in light of this decision. Free college and debt forgiveness were key issues in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, and they will continue to be key issues in contested Democratic primaries for the next several years.

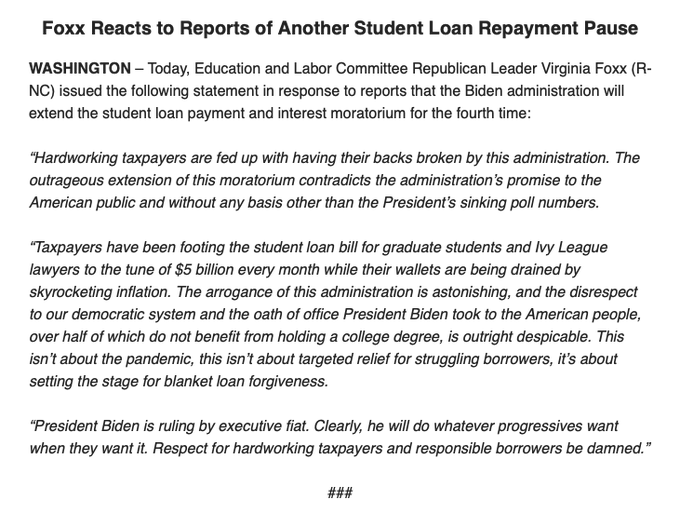

How will Republicans respond? By the time you read this, there will be plenty of press releases from Republican politicians celebrating the discussion. But there are still concerns about a future administration trying another avenue to forgiveness, particularly through income-driven repayment. There are some thoughtful efforts among Republicans to maintain income-driven repayment while reversing most of the Biden administration’s proposed changes. But Republicans are also seeking to limit borrowing for graduate students, which is something that I have been expecting for years.

This week’s Supreme Court decisions are likely to influence the direction of American higher education for years to come, and some of the influences are not going to be immediately obvious. But the items discussed above are going to play an outsized role in policy discussions for a good while.