Earlier this week, the U.S. Department of Education released its long-awaited updates to the College Scorecard website and dataset. The updated institution-level dataset has two glaring omissions that carried over from last year’s update. The first is that student loan repayment rates are no longer tracked, which is frustrating given the size of the federal government’s student loan portfolio. Taxpayers and students have the right to know whether students can manage their loans without heavy reliance on income-driven repayment. The second is that post-college earnings are excluded once again at the institution level. The program-level dataset (which I will discuss in a future post) has data, but just for graduates. That’s really useful for colleges with low graduation rates!

But in good news, this year’s Scorecard includes data on Parent PLUS loans. There are currently $101 billion in Parent PLUS Loans outstanding, $10 billion more than just two years ago. Parent PLUS loans do not count in the current cohort default rate measure, but the few studies that have gained access to PLUS data suggest that default and repayment are concerns. Because the older parents of students are expected to pay off these loans as they approach retirement, Parent PLUS loans also raise concerns about the intergenerational transmission of wealth and the growing racial wealth gap in America.

In this blog post, I dig into new Scorecard data on median Parent PLUS loan debt among 2017-18 and 2018-19 graduates, focusing on bachelor’s degree recipients attending 1,103 public and private nonprofit colleges (excluding special-focus institutions) that had sufficient data on student debt and other institutional characteristics.

First of all, the median institution had median Parent PLUS debt among borrowers of $24,399 and median student debt among borrowers of $24,250. The first graph below show that median student debt and median parent debt are only weakly correlated. This is not surprising due to the presence of loan limits for undergraduate students (a maximum of $31,000 for dependent students). But it does seem like some students turn to parent loans after hitting the cap on student loans.

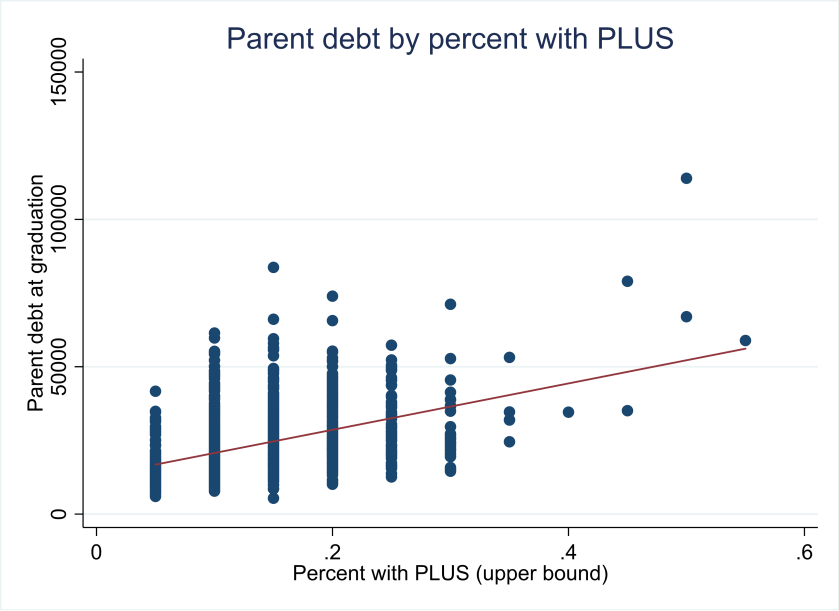

The Scorecard also provides an estimate of the percentage of students whose parents took PLUS loans, and the upper bound of the estimate is 15%. The next graph shows the relationship between the percentage of students whose parents take on loans and median parent debt. There is a positive relationship here, although this is driven in part by the small number of colleges with high borrowing rates. Very few colleges have more than 30% of parents taking on PLUS loans.

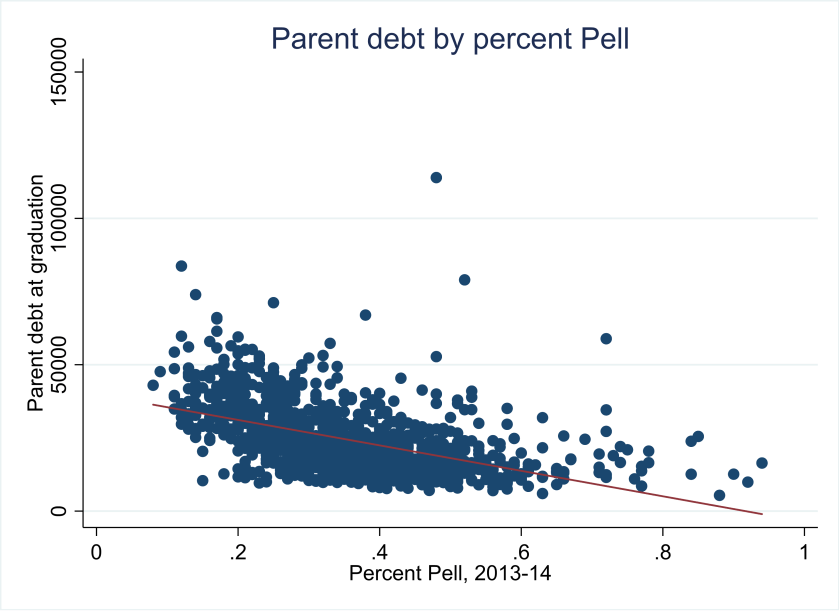

The next graph examines the relationship between Parent PLUS debt and the percentage of students who received Pell Grants in 2013-14 (the likely entry year for many of these graduates). There is a strong negative relationship, which could be due to expensive private colleges being more likely to have fewer Pell recipients. The parents of Pell recipients may also seek to borrow less money than non-Pell parents, which is strongly hinted at in Scorecard data that separates borrowing by Pell status.

Historically black colleges get a lot of attention for high Parent PLUS loan burdens, but this did not hold in my sample. The 50 HBCUs with complete data had median PLUS debt of $16,531 and median student debt of $29,502. This compared to $24,540 in PLUS debt and $24,000 in student debt for non-HBCUs. HBCU graduates likely have more in student debt because students can borrow more under their own name if their parents do not qualify for PLUS loans. The two graphs below show no consistent relationship between parent debt and the share of Black or White students.

Finally, I peeked at institutional selectivity (proxied here by ACT composite scores). As median ACT scores rose, parent debt also rose. This is likely due to selective colleges being much more expensive and parents being willing to spend lots of money to send their children there.

My next post will dive into the new program-level data, but I’m happy to take requests for additional institution-level factors to consider that could affect parent debt. This could turn into an interesting short journal article!