This post originally appeared on the Brookings Institution’s Brown Center Chalkboard blog.

The stories of financially struggling private colleges, both nonprofit and for-profit, have been told in many news articles. Small private nonprofit colleges are increasing tuition discount rates in an effort to attract a shrinking pool of traditional-age students in many parts of the country, while credit rating agency Moody’s expects the number of private nonprofit college closings to triple to about 15 per year by next year. Meanwhile, the for-profit sector has seen large enrollment decreases in the last few years amid the collapse of Corinthian Colleges and the University of Phoenix’s 50 percent drop in enrollment since 2010.

In an effort to identify financially struggling colleges and protect federal investments in student financial aid, Congress requires the U.S. Department of Education to calculate financial responsibility composite scores that are designed to measure a college’s overall financial strength based on metrics of liquidity, ability to borrow additional funds if needed, and net income. Private nonprofit and for-profit colleges are required to submit financial data each year, while public colleges are excluded under the assumption that state funding makes them unlikely to become insolvent.

Though not commonly known, these financial responsibility scores have important consequences for private colleges. Scores can range between -1.0 and 3.0, with colleges scoring at or above 1.5 being considered financially responsible and are allowed to access federal funds. Colleges scoring between 1.0 and 1.4 can access financial aid dollars, but are subject to additional Department of Education oversight of their financial aid programs. Finally, colleges scoring 0.9 or below are not considered financially responsible and must submit a letter of credit of at least 10 percent of federal student aid from the previous year and be subject to additional oversight to get access to funds. The Department of Education can also determine that a college does not meet “initial eligibility requirements due to a failing composite score” and assign it a failing grade without releasing a score to the public. In this case, a college will be immediately subject to heightened cash monitoring rules that delay the federal government’s disbursement of financial aid dollars to colleges. However, private nonprofit colleges dispute the validity of the formula, claiming it is inaccurate and does not meet current accounting standards.

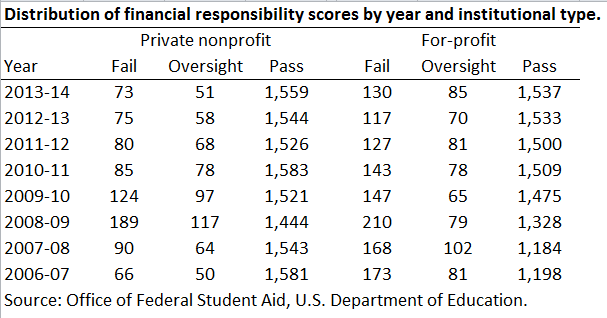

I first examined the distribution of financial responsibility scores among the 3,435 institutions (1,683 private nonprofit and 1,752 for-profit) with scores in the 2013-14 academic year, using data released to the public earlier this month. As illustrated in the figure below, only a small percentage of colleges that were assigned a score did not pass the test. In 2013-14, 203 colleges (73 nonprofit and 130 for-profit) received a failing score and an additional 136 (51 nonprofit and 85 for-profit) were in the oversight zone. Most of the colleges with failing scores are obscure institutions, such as the Champion Institute of Cosmetology in California and The Chicago School for Piano Technology. However, a few of these institutions, such as for-profit colleges Charleston School of Law, ITT Technical Institute, and Vatterott Colleges as well as nonprofit colleges Erskine College in South Carolina, Everglades University in Florida (a former for-profit) and Finlandia University in Michigan are at least somewhat better-known.

I then examined trends in financial responsibility scores since when scores were first released to the public in the 2006-07 academic year. The first finding to note in the below table is that the number of nonprofit colleges that did not pass the financial responsibility test nearly doubled between 2007-08 and 2008-09, including more than one in six institutions. Much of this increase appears to be due to the collapse in endowment values, as even a decline in a rather small endowment would affect a college’s score through reducing net income. During the same period, there was only a slight increase in the number of for-profit colleges facing additional oversight.

The second interesting trend is that in spite of concerns about the viability of small colleges with high tuition prices since the Great Recession, the number of colleges that either received a failing score or faced additional oversight has slowly declined since 2010-11. Only 12 percent of for-profits and seven percent of nonprofits failed in 2013-14, reflecting a general stabilizing trend for struggling private institutions. Although there are certainly valid concerns about how these scores are calculated, most colleges with failing scores and some others facing additional oversight are likely on shaky financial footing. Many of these colleges with failing scores—particularly for several years in a row—will be forced to consider merging with another institution or closing their doors entirely in the near future. Other colleges closer to the passing threshold may be facing tight budgets for years to come, but their short-term viability is generally secure.

It is unlikely that a substantial number of students and families know that financial responsibility scores even exist, let alone use them in their college choice decisions. However, these scores do provide some potential insights into the financial stability of a college and could potentially be included in the new College Scorecard tool. Students who are considering attending a college that repeatedly receives a failing score should ask tough questions of college officials about whether they will be financially solvent several years from now. Policymakers should use these scores as a way to identify financially struggling institutions and provide support for ones with solid academic outcomes, while also asking tough questions about the viability of cash-strapped colleges that academically underperform similar colleges.