College closures are getting quite a bit of attention right now—and for good reason. When a college closes suddenly, students are much less likely to complete their studies and employees have a difficult time finding comparable jobs. And the uptick in the number of college closures in the last year or two has been obvious to nearly everyone in higher education.

But how many colleges really close each year? The Wall Street Journal recently led off a story with a statement that more than 500 four-year private nonprofit colleges closed in the last decade, and Inside Higher Ed covered a National Center for Education Statistics report that highlighted that nearly 100 colleges closed in the 2023-24 academic year.

While I greatly appreciate Higher Ed Dive’s running list of college closures, the two more definitive sources for college closures come from the U.S. Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) and Postsecondary Education Participants System (PEPS). However, both of these sources need to be interpreted with caution due to how data are reported. I discuss my recommendation for using IPEDS and PEPS below, and see this spreadsheet for the data that I refer to throughout the piece.

IPEDS

IPEDS has a rough measure of college closures in its Directory Information data collection, which is updated annually. The relevant variable is whether an institution is active in the current year, with the possible answers of “yes” or “no: closed, combined, or out-of-scope.” The challenge here is that a substantial number of colleges included under “no” fall under the combined and out-of-scope categories without any disruption to students. Combined institutions can be the result of one college acquiring another, but it can also be an administrative consolidation for reporting purposes that does not change anything for students. An out-of-scope college may choose to opt out of federal Title IV financial aid programs while remaining open; this is primarily the case among for-profit colleges.

In the 2023-24 academic year, I count 70 primarily postsecondary institutions (IPEDS also includes some vocational training programs that are mainly secondary schools, but I exclude them here) that left the IPEDS universe. A complete list of these apparent closures can be found in the first tab of this spreadsheet.

Some of the institutions are clearly closures (such as Finlandia University in Michigan and Medaille University in New York), but others are administrative consolidations. For example, 11 of the 70 “closures” are community colleges in Connecticut, which recently moved to a single-institution model with 12 branch campuses (no campuses were closed).

Similar examples of administrative consolidations are visible at public colleges in Tennessee and Vermont. The private nonprofit closures are primarily freestanding institutions, while quite a few for-profit college closures include multiple branches closing at the same time. Overall, it appears that roughly 40 unique institutions (excluding branches) actually closed in 2023-24, and they are divided between for-profit and nonprofit colleges.

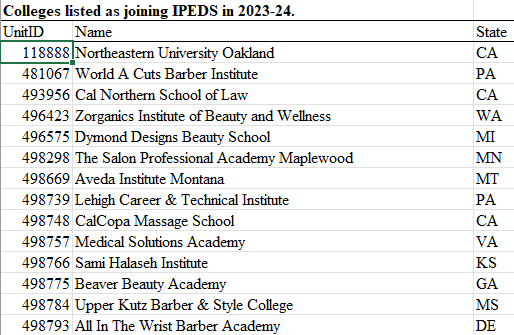

On the other hand, 56 colleges joined the IPEDS universe in the 2023-24 academic year (the second tab of the spreadsheet). They are primarily small, vocationally focused for-profit colleges that frequently cycle in and out of operation. But I did notice Northeastern University Oakland on the list of newly opened colleges using the same IPEDS UnitID as Mills College. It is relatively uncommon for private nonprofit colleges to open and receive federal financial aid, but it occasionally happens in special-focus fields such as health sciences and technical education.

PEPS

If you have read to this point in a pretty technical blog post, you have some pep in your step. Federal Student Aid updates the PEPS data page weekly with a list of every college that closes. That sounds great—until you go and download the spreadsheet. This behemoth (accessible by downloading the closed school search file) includes more than 20,000 college closures since the mid-1980s.

That number of closures seems a bit high since there are only about 6,000 colleges receiving federal financial aid in the United States at this point. The reason is that PEPS tracks the closure of every single physical campus location in the United States, as well as foreign locations of American-based or Title IV-eligible institutions. Let’s look at 2024 PEPS data, which I included in the third tab of the spreadsheet.

PEPS lists 81 closures in 2024, with the most recent closure being on August 9. But as the below picture shows, many of these closures are of small branch campuses. For example, Saint Louis University closed small sites in Jefferson City, Dallas, and Houston. Johns Hopkins University closed seven sites in Texas, for crying out loud! Other closures are real and meaningful, such as Goddard College and UW-Oshkosh’s Fond du Lac campus (which was a freestanding institution until several years ago).

The way to identify a main campus closure is through examining the Office of Postsecondary Education ID (OPEID) number. If the number starts with a zero and ends in 00, that is a main campus. Any OPEID that ends in something other than 00 (or starts with a number other than zero) is a branch campus. Many of these branches often enroll a small number of students and come and go regularly, although a few are more notable. Thirty-two of the 81 closures to this point in 2024 have been main campuses, while the rest were branch campuses.

So how many colleges really close each year? It depends a lot on what you consider to be a college. But I would contend that quite a few of the colleges listed in federal data as closing either did not actually close or served a minuscule number of students at offsite locations. This does not make the closure of main campuses less concerning, but it’s important to have a clear sense of the numbers before engaging in policy discussions.