The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid released its newest quarterly update on federal student loan and Pell Grant awards on Friday, and the data (through the end of the 2014-15 academic year) are nothing short of stunning. As shown in the table below, federal student loan volume dropped by nearly $11 billion in 2014-15 to $89.4 billion, the lowest level since before the federal government ended the old bank-based lending program in 2010. Total Pell Grant awards also declined in 2014-15 to $30.3 billion, more than $5 billion below 2010-11 levels. (For more on trends in Pell awards over the last two decades, see my recent post on the topic.)

What could explain such sharp drops in student loan and Pell Grant dollars? Four factors could be at work:

(1) As America slowly continues to climb out of the Great Recession, more students and families may be earning enough money not to qualify for Pell Grants or need to borrow as much in student loans. Unemployment rates are down sharply since 2010, but median real household income has been nearly flat—so this is probably a minor contributing factor.

(2) Americans may be less willing to borrow for college than they were a few years ago, leading to less student loan debt. I’m more concerned about undergraduate students underborrowing for college than overborrowing, particularly as students react to stories about other people’s (atypical) debt loads and concerns about their financial strength. But this is difficult to prove empirically given current data.

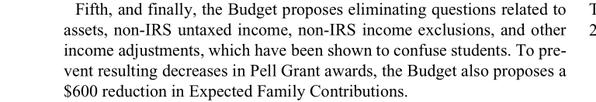

(3) Part of the decline in total Pell awards is likely due to changes in the FAFSA formula that reduced the number of students automatically receiving the maximum Pell Grant in 2012-13 and beyond. But this would not explain continued declines in Pell dollars received.

(4) The most likely explanation to me is decreased enrollment due to an improved labor market inducing some individuals to work instead of attend college combined with the collapse of some of the large for-profit college chains. The most up-to-date data from the National Student Clearinghouse (which is available well ahead of federal estimates) show that enrollment has declined at degree-granting colleges each of the past three years, with the largest declines taking place at community colleges and in the for-profit sector. Lower enrollment, particularly among adult students, leads to fewer students taking out loans and receiving Pell Grants.

As the economy continues to slowly strengthen and the for-profit sector continues to sort itself out, I would expect enrollment (and the number of students receiving Pell Grants) to very slowly increase over the next several years. Future trends in student loan debt are less clear. Given the explosion of students enrolling in income-based repayment programs, students (particularly in graduate programs) might have less of an incentive to keep loan amounts in check. Yet, to this point, there doesn’t seem to be a boom in graduate school loans across the board. It would be worth looking at particular colleges with large programs in fields that are especially likely to qualify for Public Service Loan Forgiveness to see if loan amounts there are up by large amounts.