I thought that the end of 2025 was going to be relatively quiet when I wrote my last piece a couple of weeks ago, but my words to the Chronicle of Higher Education for their 25-year retrospective came back to bite me:

“It’s hard not to focus just on what has happened in 2025, because it seems like this year alone has been 25 years long.”

So I’m back with one more piece on New Year’s Eve before I throw a standing rib roast in the smoker to celebrate the coming of 2026. On December 30, the Department of Education released several new datasets on program-level outcomes in advance of early January’s negotiated rulemaking session on implementing accountability provisions set in place by last July’s budget reconciliation law (OBBB) that effectively served as a reauthorization of the Higher Education Act.

The key focus of the rulemaking session will be to determine whether there should be one or two accountability systems. Currently, gainful employment regulations focus on for-profit institutions and certificate programs at other institutions and base calculations on a debt-to-earning metrics. The new system approved by Congress in OBBB, however, excludes undergraduate certificates and bases passing on whether earnings are higher than a complicated threshold metric four years after completion. By also limiting loans to graduate students, the debt-to-earnings threshold is arguably less important now than in the past, making a good argument for a single metric for graduate students. But for undergraduates, debt is still a somewhat useful metric, although I do not know whether two systems would be worth the hassle.

This is a substantial dataset that goes well beyond the minimum needed to implement accountability, and I applaud the skeleton staff at the Department of Education for getting this done. I have pointed out issues with the first two IPEDS data releases of the second Trump administration, but this one seems to have gone quite well. This also means that ED and the Internal Revenue Service have figured out interagency cooperation to update earnings data, meaning that a big College Scorecard update is also likely to come. I am still quite worried about ED’s ability to manage the huge proposed admissions data collection, so stay tuned on the data front.

The most important new program-level data elements are the following:

- Noncompletion rate: This is defined as a student who received federal financial aid in a given year and then does not show up as a graduate or enrolled as a federal aid recipient in the next two years. This is a pretty generous definition in terms of allowing students to transfer programs or institutions, but it can also miss students who no longer receive federal aid. I’m watching the metric closely, but am not sure about using it yet.

- Earnings: We finally get a new cohort of earnings data! For years, the program-level Scorecard has focused on students who graduated in 2014-15 or 2015-16, and that now gets refreshed to 2017-18 and 2018-19 graduates. This makes it possible to track changes in earnings across multiple cohorts, which is neat.

- The number of financial aid recipients and grant/loan disbursements by program: This is brand-new data, and it is available for ten years (Fiscal Years 2016 through 2025).

- OBBB earnings metric status: This compares the four-year earnings metric to the threshold, which is essentially what the student is estimated to have earned if they did not pursue that credential. Failing that metric in two of three consecutive years will subject the program to the loss of federal loan eligibility.

I am focusing on two key questions in the rest of this blog post, and I put together a dataset for download that contains the 91,989 programs with at least some data (just under half of all programs, as defined at the 4-digit CIP level).

Question 1: Which programs would fail the earnings threshold metric?

Overall, 2,964 of the 49,860 programs (5.9%) with sufficient data on program-level earnings are estimated to be below the earnings threshold. But there is a lot of variation by institution type, credential level, and field of study.

| Pass | Fail | Failure rate | |

| For-profit | 2,345 | 1,268 | 35.1% |

| Nonprofit | 14,446 | 492 | 3.3% |

| Public | 30,105 | 1,204 | 3.8% |

This is a bit of an eye-popping number—programs at for-profit colleges are about ten times more likely to fail than other sectors. But let’s dig deeper. Credential level matters a lot, with quite a few undergraduate certificates (which are not a part of the OBBB) failing. The failure rates by sector and credential level are not quite as jarring for the for-profit sector.

| Public | Private nonprofit | For-profit | |

| Undergrad certificate | 13.3% | 28.5% | 55.8% |

| Associate | 5.9% | 8.2% | 12.0% |

| Bachelor | 1.0% | 1.4% | 3.8% |

| Post-bacc certificate | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Master’s | 3.1% | 6.2% | 12.0% |

| Graduate certificate | 3.8% | 3.9% | 5.3% |

| First professional | 0.0% | 3.0% | 31.3% |

| Doctoral | 0.2% | 2.2% | 0.0% |

I then looked by some of the most common fields of study (by 2-digit CIP code). Here is how the fields with at least 1,000 programs fared:

| Field | Failure rate |

| Biology | 1.1% |

| Business | 1.8% |

| Communications | 2.5% |

| Computer science | 1.2% |

| Education | 2.9% |

| Engineering | 0.0% |

| Health | 8.3% |

| Liberal arts | 4.2% |

| Personal/culinary services | 78.5% |

| Psychology | 2.3% |

| Public administration | 1.9% |

| Security | 1.2% |

| Social sciences | 1.3% |

| Visual/performing arts | 17.7% |

In general, most fields do pretty well (and engineering had exactly zero programs fail). But personal/culinary services, which is a field with a lot of undergraduate certificates (and tips for earnings that are not reported to the IRS), and visual and performing arts perform much worse.

Question 2: Which programs are facing challenges with reduced graduate student loan limits?

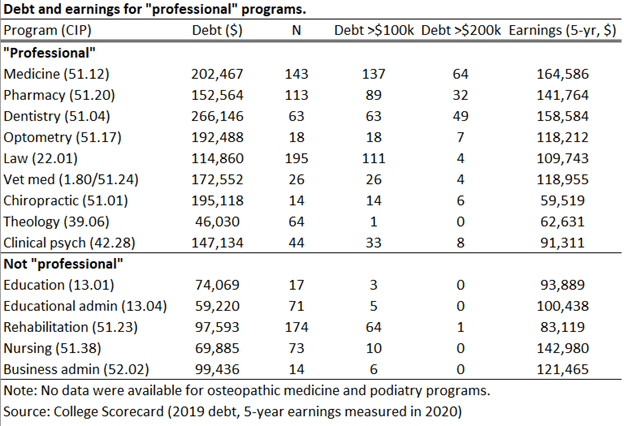

Effective July 1, 2026 (with the exception of some programs that are granted a brief reprieve), only a short list of so-called “professional” programs can access $50,000 per year in federal student loans and $200,000 during the entire length of the program. All other “graduate” programs are limited to $20,500 per year and $100,000 for the entire program. Based on my coding of the relevant CIP codes and the available data, I see 1,120 programs with available data as likely being professional and 17,297 programs likely being graduate.

The bad news for higher education is that quite a few programs have average debt (among borrowers) that is above these annual limits. Thirty percent of professional programs and 26% of graduate programs are over their caps, and in some cases well over the caps. For example, 461 graduate programs have more than $50,000 per year in annual borrowing and 20 professional programs (mostly in dentistry) have more than $100,000 per year in annual borrowing.

There are also differences by field of study in the number of programs over their loan limits. Of the most popular graduate programs (at least 450 observations), nearly half of health and biology programs averaged over the $20,500 annual limit among borrowers. Education, as usual, had the lowest rate of overages. Among professional programs, half of all health-related and veterinary medicine programs were over $50,000 per year in average debt. One-fourth of law schools exceeded the new limit, while only nine of 211 psychology programs and zero theology programs were in excess of $50,000.

| Field | Over the limit (pct) |

| Biology | 46.8% |

| Business | 18.8% |

| Computer science | 21.7% |

| Education | 8.7% |

| Health | 46.9% |

| Multidisciplinary studies | 30.7% |

| Psychology | 22.1% |

| Public administration | 21.8% |

| Visual/performing arts | 37.8% |

There is a lot more in this dataset, and there is always the possibility of additional data releases next week as negotiators ask for additional information. But for now, Happy New Year!