Today is a red-letter day for many people in the higher education community—the release of the annual college rankings from U.S. News and World Report. While many people love to hate the rankings for an array of reasons (from the perceived focus on prestige to a general dislike of accountability in some sectors), their influence on colleges and universities is undeniable. Colleges love to put out press releases touting their place in the rankings even while decrying their general premise.

I’m no stranger to the college ranking business, having been the consulting methodologist for Washington Monthly’s annual college rankings for the past two years. (All opinions in this piece, of course, are my own.) While Washington Monthly’s rankings rank colleges based on social mobility, service, and research performance, U.S. News ranks colleges primarily based on “academic quality,” which consists of inputs such as financial resources and standardized test scores as well as peer assessments for certain types of colleges.

I’m not necessarily in the U.S. News-bashing camp here, as they provide a useful service for people who are interested in prestige-based rankings (which I think is most people who want to buy college guides). But the public policy discussion, driven in part by the President’s proposal to create a college rating system, has been moving toward an outcome-based focus. The Washington Monthly rankings do capture some elements of this focus, as can be seen in my recent appearance on MSNBC and an outstanding panel discussion hosted by New America and Washington Monthly last week in Washington.

Perhaps in response to criticism or the apparent direction of public policy, Robert Morse (the well-known and well-respected methodologist for U.S. News) announced some changes last week in the magazine’s methodology for this year’s rankings. The changes place slightly less weight on peer assessment and selectivity, while putting slightly more weight on graduation rate performance and graduation/retention rates. Yet Morse bills the changes as meaningful, noting that “many schools’ ranks will change in the 2014 [this year’s] edition of the Best Colleges rankings compared with the 2013 edition.”

But the rankings have tended to be quite stable from year to year (here are the 2014 rankings). The top six research universities in the first U.S. News survey (in 1983—based on peer assessments by college presidents) were Stanford, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Berkeley, and Chicago, with Amherst, Swarthmore, Williams, Carleton, and Oberlin being the top five liberal arts colleges. All of the research universities except Berkeley are in the top six this year and all of the liberal arts colleges except Oberlin are in the top eight.

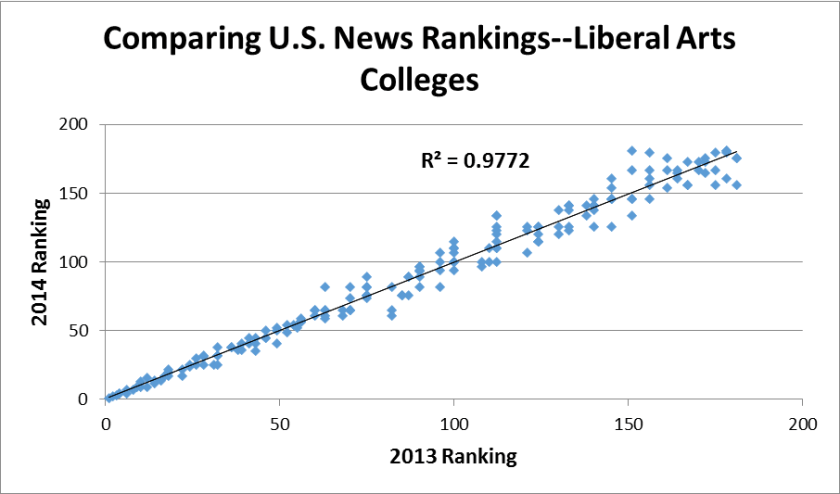

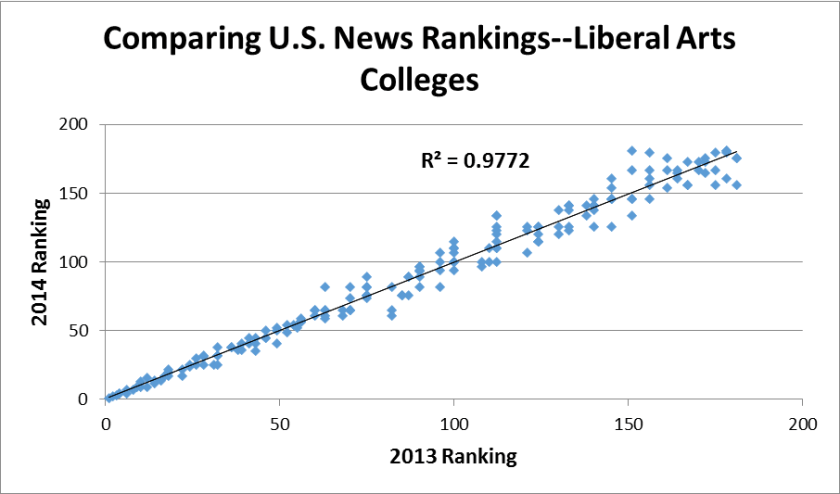

In this post, I’ve examined all national universities (just over 200) and liberal arts colleges (about 180) ranked by U.S. News in this year’s and last year’s rankings. Note that this is only a portion of qualifying colleges, but the magazine doesn’t rank lower-tier institutions. The two graphs below show the changes in the rankings for national universities and liberal arts colleges between the two years.

The first thing that jumps out at me is the high R-squared, around 0.98 for both classifications. What this essentially means is that 98% of the variation in this year’s rankings can be explained by last year’s rankings—a remarkable amount of persistence even when considering the slow-moving nature of colleges. The graphs show more movement among liberal arts colleges, which are much smaller and can be affected by random noise much more than large research universities.

The biggest blip in the national university rankings is South Carolina State, which went from 147th last year to unranked (no higher than 202nd) this year. Other universities which fell more than 20 spots are Howard University, the University of Missouri-Kansas City, and Rutgers University-Newark, all urban and/or minority-serving institutions. Could the change in formulas have hurt these types of institutions?

In tomorrow’s post, I’ll compare the U.S. News rankings to the Washington Monthly rankings for this same sample of institutions. Stay tuned!