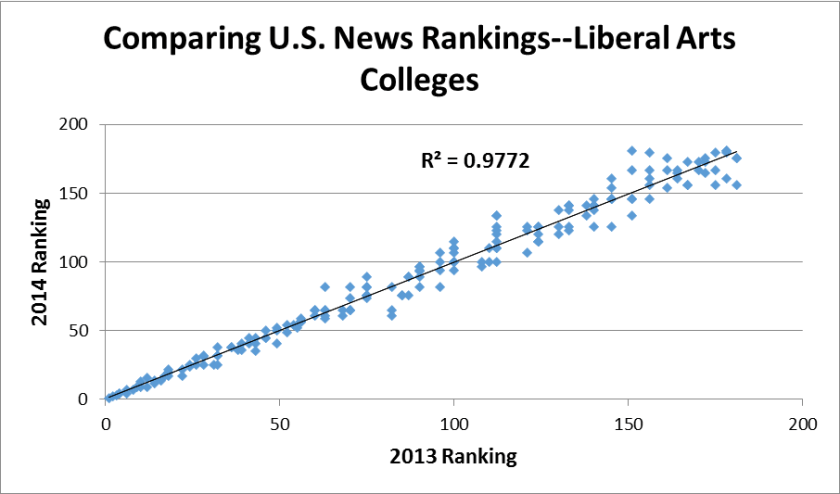

In yesterday’s post, I discussed the newly released 2014 college rankings from U.S. News & World Report and how they changed from last year. In spite of some changes in methodology that were billed as “significant,” the R-squared value when comparing this year’s rankings with last year’s rankings among ranked national universities and liberal arts colleges was about 0.98. That means that 98% of the variation in this year’s rankings can be explained by last year’s rankings—a nearly perfect prediction.

In today’s post, I compare the results of the U.S. News rankings to those from the Washington Monthly rankings for national universities and liberal arts colleges ranked by both sources. The rankings from Washington Monthly (for which I’m the consulting methodologist and compiled them) are based on three criteria: social mobility, research, and service, which are not the particular goals of the U.S. News rankings. Yet it could still be the case that colleges that recruit high-quality students, have lots of resources, and have a great reputation (the main factors in the U.S. News rankings) do a good job recruiting students from low-income families, produce outstanding research, and graduate servant-leaders.

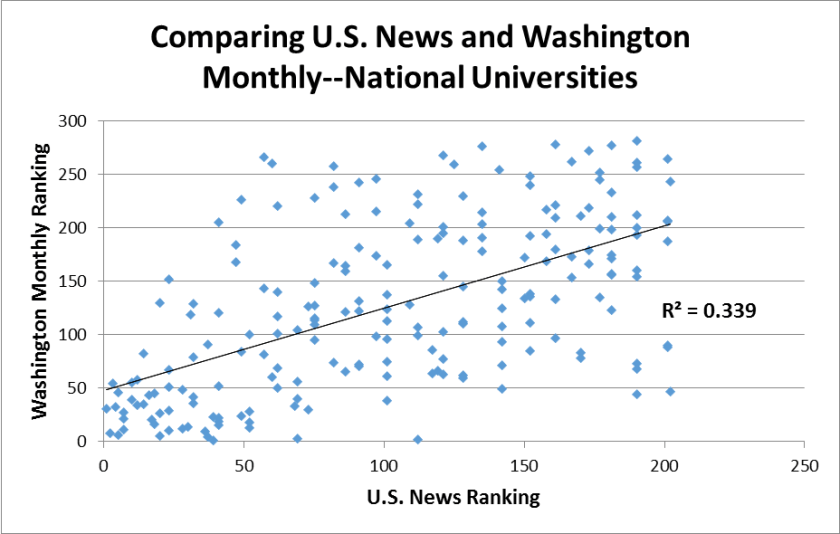

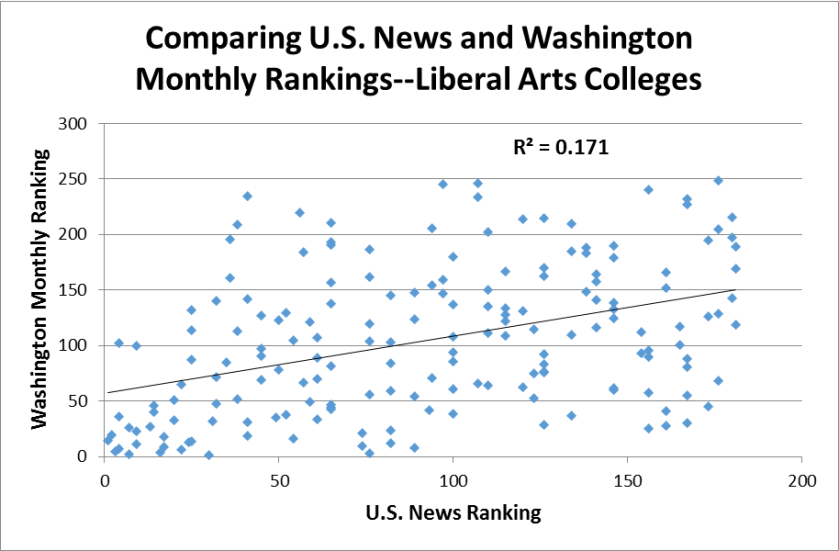

The results of my comparisons show large differences between the two sets of rankings, particularly at liberal arts colleges. The R-squared value at national universities is 0.34, but only 0.17 at liberal arts colleges, as shown below:

It is worth highlighting some of the colleges that are high on both rankings. Harvard, Stanford, Swarthmore, Pomona, and Carleton all rank in the top ten in both magazines, showing that it is possible to be both highly selective and serve the public in an admirable way. (Of course, we should expect that to be the case given the size of their endowments and their favorable tax treatment!) However, Middlebury and Claremont McKenna check in around 100th in the Washington Monthly rankings in spite of a top-ten U.S. News ranking. These well-endowed institutions don’t seem to have the same commitment to the public good as some of their highly selective peers.

On the other hand, colleges ranked lower by U.S. News do well in the Washington Monthly ranking. Some examples include the University of California-Riverside (2nd in WM, 112th in U.S. News), Berea College (3rd in WM, 76th in U.S. News), and the New College of Florida (8th in WM, 89th in U.S. News). If nothing else, the high ranks in the Washington Monthly rankings give these institutions a chance to toot their own hour and highlight their own successes.

I fully realize that only a small percentage of prospective students will be interested in the Washington Monthly rankings compared to those from U.S. News. But it is worth highlighting the differences across college rankings so students and policymakers can decide what institutions are better for them given their own demands and preferences.