The National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators jumped into the financial aid reform debate this week with the release of their policy paper as a part of the Gates Foundation’s Reimagining Aid Delivery and Design (RADD) project. Many of the recommendations are similar to other papers in the panel (including proposals to increase the maximum Pell Grant for certain students and providing more information for students and their families to make better college decisions)—and an additional recommendation of exploring an early commitment program for Pell recipients is informed by some of my research, which is pretty nifty.

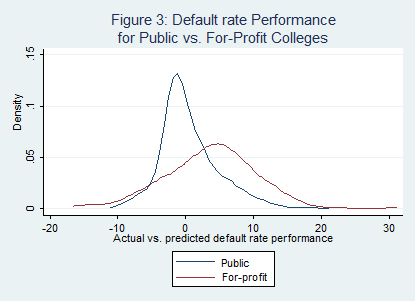

The NASFAA report does make one recommendation which will likely prove to be highly controversial—limiting eligibility for student loans for certain groups of students in a clear effort to reduce student loan default rates. First, NASFAA suggests that students who do not meet a baseline level of academic preparation (perhaps a combination of ACT/SAT scores and high school GPA) would not be initially eligible to take out federal student loans. This proposal would be similar to the academic eligibility index used by the NCAA to determine student-athletes’ ability to play college sports. This proposal could have the effect of ending the open-access institution as we know it, depending on exactly where the cutoff is set. While it is true that students with lower standardized test scores are less likely to complete college, I’m very hesitant to place a substantial barrier to college entry—especially for students who did not enroll in college directly after completing high school.

The report also contains a recommendation allowing colleges to restrict groups of students’ ability to borrow if the financial aid officer feels that the loan funds are not needed or risky. For example, education majors’ loans may be limited compared to business majors because of their lower annual earnings (and reduced repayment abilities). Restricting access to loans by program characteristics (instead of individual characteristics) reduces the burden on financial aid officers, but also fails to take individual characteristics into account unless a student appeals for professional judgment.

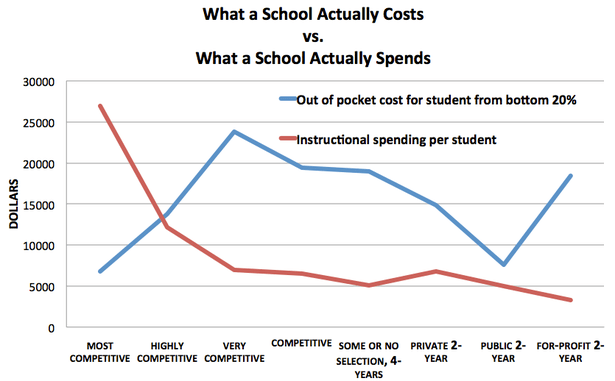

The proposal to limit student loans will penalize students who cannot pay for college by any other means—especially for dependent students who cannot get parental support to pay for their expected family contribution. Additionally, many students cannot borrow the maximum amount of loans under current rules, which base eligibility in part on the estimated cost of attendance. Research suggests that this posted cost of attendance may be much lower than the actual cost of attending college, as institutions have an incentive to make the college look as affordable as possible.

While I am concerned about these particular portions of NASFAA’s proposal, they raise concerns that are of genuine merit and concern in the financial aid and policy communities. I would be surprised if they become a part of federal rules in any meaningful way, but this does show the diversity of opinions within the RADD group and the importance of listening to as many stakeholders as possible before redesigning the financial aid system.