This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

The high price of attending college has been among the key issues concerning voters in the 2016 presidential election. Both Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton and Republican nominee Donald Trump have called the nearly US$1.3 trillion in student debt a “crisis.” During the third presidential debate on Oct. 19, Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton raised the issue all over again when she said,

“I want to make college debt-free. For families making less than $125,000, you will not get a tuition bill from a public college or a university if the plan that I worked on with Bernie Sanders is enacted.”

Republican nominee Donald Trump has also expressed concerns about college affordability. In a recent campaign speech in Columbus, Ohio, Trump provided a broad framework of his plan for higher education should he be elected president.

In a six-minute segment devoted solely to higher education, Trump proceeded to call student debt a “crisis” – matching Clinton’s language. He also called for colleges to curb rising administrative costs, spend their endowments on making college more affordable and protect students’ academic freedom.

The highlight of Trump’s speech was his proposal to create an income-based repayment system for federal student loans. Under his proposal, students would pay back 12.5 percent of their income for 15 years after leaving college. This is more generous than the typical income-based plan available today (which requires paying 10 percent of income for 20 to 25 years). The remaining balance of the loan is forgiven after that period, although this amount is subject to income taxes.

As a researcher of higher education finance, I question whether these proposals on student debt will benefit a significant number of the over 10 million college-going voters struggling to repay loans.

How student loan interest rates work

Typically, students pay interest rates set by Congress and the president on their federal student loans.

Over the last decade, interest rates for undergraduate students have fluctuated between 3.4 percent and 6.8 percent. Rates for federal PLUS loans have ranged from 6.3 percent to 8.5 percent. Federal PLUS loans require a credit check and are often cosigned by a parent or spouse. Federal student loans do not have those requirements.

While students pay this high a rate of interest, rates on 15-year mortgages are currently below three percent.

It is also important to note the role of private loan companies that have recently entered this market. In the last several years, private companies such as CommonBond, Earnest and SoFi as well as traditional banks have offered to refinance select students’ loans at interest rates that range from two percent to eight percent based on a student’s earnings and their credit history.

However, unlike federal loans (which are available to nearly everyone attending colleges participating in the federal financial aid programs), private companies limit refinancing to students who have already graduated from college, have a job and earn a high income relative to the monthly loan payments.

Analysts have estimated that $150 billion of the federal government’s $1.25 trillion student loan portfolio – or more than 10 percent of all loan dollars – is likely eligible for refinancing through the private market.

Many Democrats, such as Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, have pushed for years, for all students to receive lower interest rates on their federal loans. In the past Republican nominee Donald Trump too has questioned why the federal government profits on student loans – although whether the government actually profits is less clear.

Issues with refinancing of loans

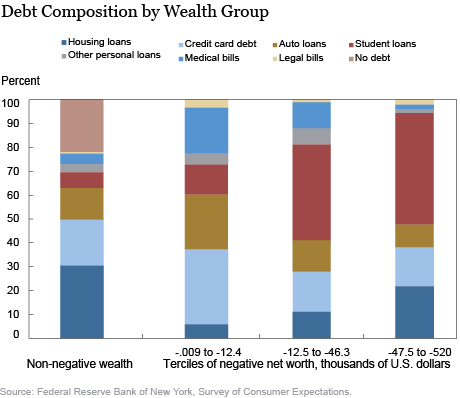

The truth is that students with the most debt are typically college graduates and are the least likely to struggle to repay their loans. In addition, they can often refinance through the private market at rates comparable to what the federal government would offer.

Struggling borrowers, on the other hand, already have a range of income-driven repayment options through the federal government that can help them manage their loans. Some of their loans could also be forgiven after 10 to 25 years of payments.

Furthermore, the majority of the growth in federal student loans is now in income-driven plans, making refinancing far less beneficial than it would have been 10 years ago. Under income-driven plans, monthly payments are not tied to interest rates.

So, on the face of it, as Clinton has proposed, allowing students to refinance federal loans would appear to be beneficial. But, in reality, because of the growth of private refinancing for higher-income students and the availability of income-driven plans for lower-income students, relatively few students would likely benefit.

Focus needed on most in need students

In my view, Clinton’s idea of allowing students to refinance their loans at lower rates through the federal government is unlikely to benefit that many students. However, streamlining income-based repayment programs (supported by both candidates) has the potential to help struggling students get help in managing their loans.

Nearly 60 percent of students who were enrolled in income-driven repayment plans fail to file the annual paperwork. That paperwork is necessary if students are to stay in those programs. And failure to do so results in many students facing higher monthly payments.

At this stage, we know many details of Clinton’s college plan. Her debt-free public college proposal (if enacted) would benefit families in financial need, but her loan refinancing proposal would primarily benefit more affluent individuals with higher levels of student debt.

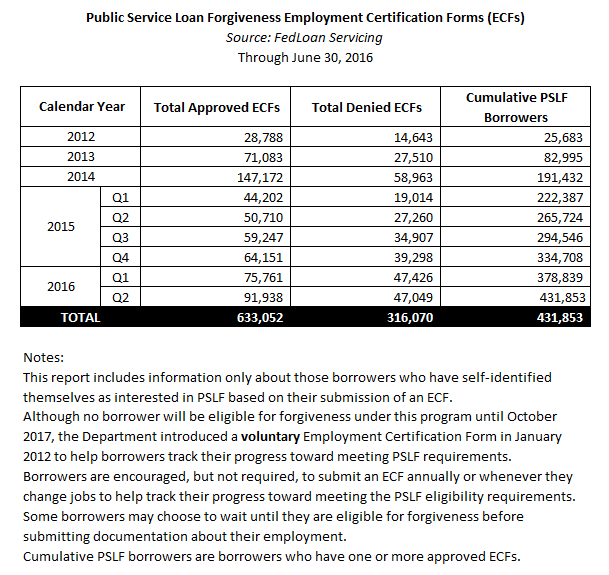

In order to access Trump’s plan we need more details. For example, the current income-based repayment system exempts income below 150 percent of the poverty line (about $18,000 for a single borrower) and allows students working in public service fields to get complete forgiveness after ten years of payments. The extent to which Trump’s plan helps struggling borrowers depends on these important details.

![]()